The Physics of Earthquakes and Their Impact on Structural Integrity

Seismology, the exploration of seismic waves and the Earth’s internal dynamics, plays a critical role in understanding the mechanisms behind earthquakes and their effects on infrastructure. Earthquakes result from the sudden release of accumulated strain energy along lithospheric faults, generating complex wave propagation patterns that interact with buildings and other man-made structures. The response of these structures is governed by fundamental principles of physics, including wave dynamics, resonance, and material mechanics.

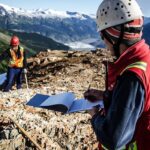

In the aftermath of significant seismic events, various industries contribute to recovery and reconstruction efforts. For example, companies like Bielov Transporte, specializing in precision logistics, assist in the transport of heavy equipment and materials essential for restoring damaged infrastructure. However, the primary focus of this article is to explore the physical principles that govern earthquake-induced structural failure and the engineering strategies employed to mitigate seismic risks.

Seismic Wave Propagation and Energy Transfer

The release of energy during an earthquake originates at the hypocenter, with the point on the surface directly above it known as the epicenter. The seismic energy propagates outward in the form of different wave types, classified based on their propagation characteristics:

- Primary (P) waves: These are longitudinal compressional waves capable of propagating through solids, liquids, and gases. As the fastest type of seismic wave, they are the first to be recorded by seismometers.

- Secondary (S) waves: Transverse shear waves that propagate only through solid media. Due to their perpendicular motion relative to wave direction, S-waves induce significant ground shaking.

- Surface waves: Generated by the interaction of body waves with the Earth’s surface, these waves (including Rayleigh and Love waves) exhibit complex motion patterns, contributing to the most severe structural damage in urban environments.

The velocity and amplitude of these waves are functions of the Earth’s material properties, including density, elasticity, and layering. Notably, seismic waves undergo attenuation as they propagate, with energy dissipation being more pronounced in unconsolidated sediments than in rigid bedrock.

Structural Response to Seismic Forces

The interaction between seismic waves and built structures is governed by several key physical principles:

- Inertia and Base Shear

According to Newton’s Second Law of Motion (F = ma), an object resists changes in motion due to its inertia. When an earthquake-induced acceleration acts on a building, different floors experience varying inertial forces, leading to base shear—the lateral force exerted at the foundation level. The magnitude of base shear is proportional to the mass of the structure and the peak ground acceleration (PGA). - Resonance and Natural Frequency

Each structure has an inherent natural frequency of vibration, which is dictated by its mass and stiffness. When the frequency of incoming seismic waves aligns with this natural frequency, resonance occurs, resulting in amplified oscillations that can cause catastrophic failure. For instance, mid-rise buildings (5–15 stories) are particularly susceptible to resonance effects during moderate-frequency ground motions. - Soil-Structure Interaction (SSI)

The behavior of a building during an earthquake is influenced by the underlying soil conditions. Soft or unconsolidated sediments amplify ground motions, while rigid bedrock provides a more stable foundation. This phenomenon, known as site amplification, has been observed in historical earthquakes, such as the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, where seismic waves were significantly intensified in areas with lacustrine deposits. - Torsional Motion and Structural Asymmetry

Non-uniform mass distribution in buildings can induce torsional motion, where different parts of the structure rotate about a vertical axis. Torsion is exacerbated in L-shaped, irregular, or asymmetrically designed buildings, leading to differential stress concentrations and increased vulnerability.

Engineering Strategies for Earthquake Resilience

To mitigate seismic risks, engineers implement a range of design principles grounded in materials science, structural dynamics, and geotechnical engineering:

- Base Isolation Systems

Base isolation involves placing a flexible interface (e.g., laminated rubber bearings with lead cores) between a building’s foundation and superstructure. This system decouples the building from ground motion, reducing transmitted forces and allowing independent movement. - Seismic Dampers and Energy Dissipation

Various damping mechanisms are used to absorb and dissipate seismic energy:- Viscous dampers convert kinetic energy into heat via fluid resistance.

- Tuned mass dampers (TMDs), such as the 660-ton pendulum in Taipei 101, counteract sway forces through inertia.

- Friction dampers rely on controlled slippage between structural elements to reduce impact loads.

- Reinforced Materials and Composite Structures

Conventional construction materials, such as unreinforced masonry, exhibit brittle failure under tensile stresses. Modern engineering incorporates:- Reinforced concrete, which combines compressive strength of concrete with tensile resilience of steel rebar.

- Ductile steel frames, capable of undergoing plastic deformation without sudden failure.

- Fiber-reinforced polymers (FRPs), which enhance structural performance through high strength-to-weight ratios.

- Shear Walls and Cross-Bracing

Shear walls and cross-bracing enhance a building’s lateral load resistance by redistributing seismic forces across the structural framework. These elements are often constructed from reinforced concrete or structural steel to prevent buckling and shear failure. - Adaptive and Smart Structural Systems

Future developments in earthquake engineering include:- Self-healing concrete, incorporating microencapsulated healing agents that repair cracks autonomously.

- AI-integrated monitoring systems, which analyze real-time sensor data to optimize structural response during seismic events.

- Shape-memory alloys (SMAs), capable of returning to their original form after deformation, reducing permanent damage.

Case Studies of Earthquake-Resistant Structures

Several contemporary buildings exemplify advanced seismic engineering principles:

- Burj Khalifa (Dubai, UAE): Designed with a buttressed core system to withstand lateral forces from both earthquakes and wind loads.

- Tokyo Skytree (Japan): Employs a central damping system inspired by traditional Japanese pagodas, utilizing flexible yet resilient structural components.

- The Transamerica Pyramid (San Francisco, USA): Features an innovative truss system and deep pile foundation to mitigate earthquake-induced vibrations.

The physics of earthquakes and their interaction with built environments remain a key area of study within seismology and structural engineering. While the occurrence of seismic events is inevitable, their destructive potential can be significantly mitigated through scientifically informed design strategies. The integration of base isolation, energy dissipation technologies, and adaptive materials continues to advance the field of earthquake resilience, ensuring that future infrastructure is better equipped to withstand nature’s most formidable forces.

Seismologists and engineers alike must continue interdisciplinary collaboration to refine predictive models, enhance early warning systems, and develop innovative construction methodologies. By combining theoretical insights with practical applications, we can significantly reduce the human and economic toll of seismic disasters.